My father always had charcoal, sketchbooks, oil pastels, and other art supplies around the house when I was growing up, and as a child, you used them in whatever way you could think of. I have always loved painting and drawing, but after taking one class in college, I never picked it up again. I had high expectations for the final pieces, but the drawings I produced were never up to par (in my mind). I found that when people would talk about what made a “good” painting, they meant how close to reality it resembled. Having moved to France in 2018, and being a few minutes away from some of the most renowned art museums in the world, I took the time to study the paintings that intrigued me the most, and in that, I found like-minded people who also admired the chaos and beauty of unrealistic paintings.

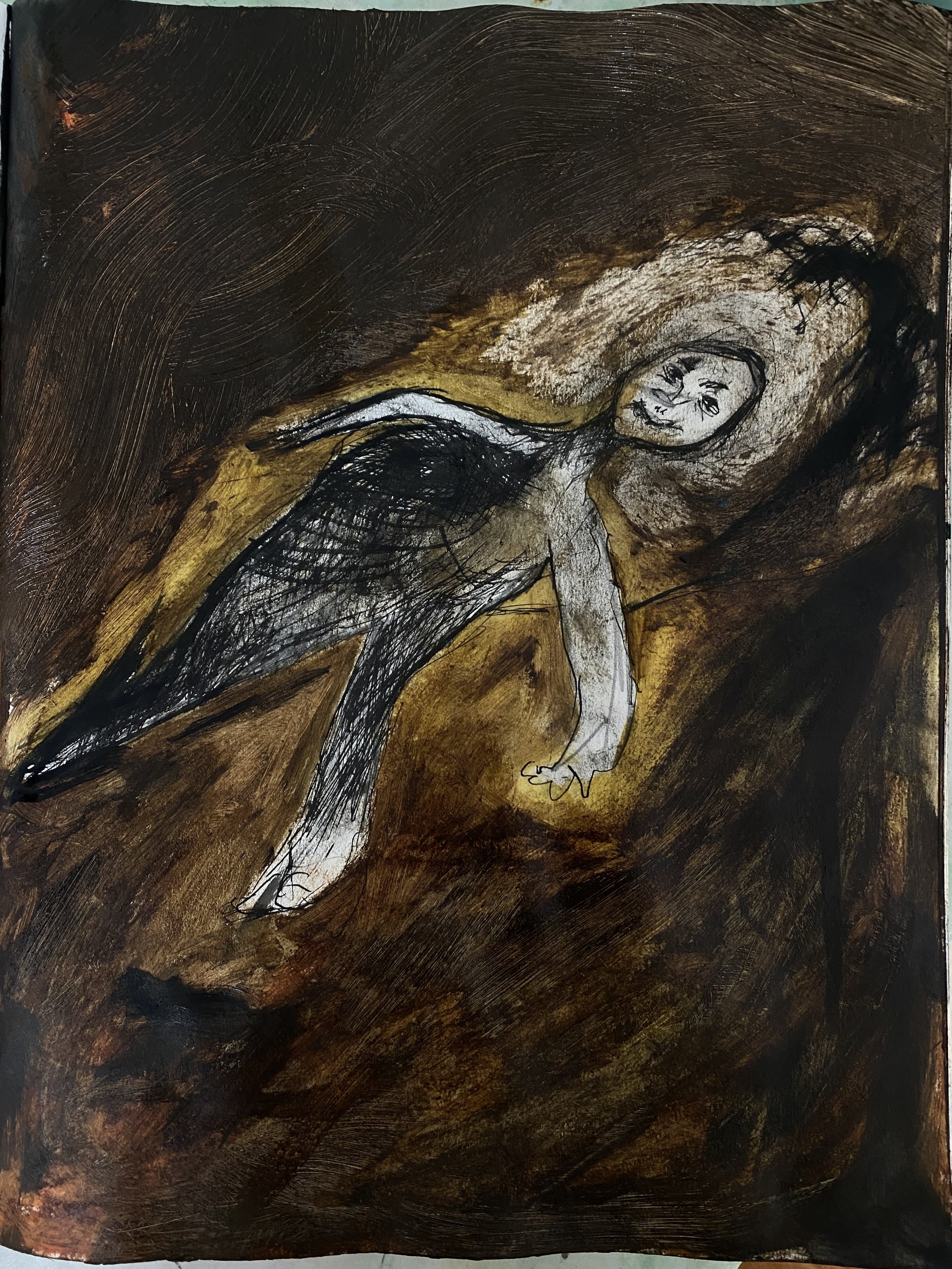

2020 was the year I finally permitted myself to paint because we were all cooped up inside with nothing to do. I decided to interpret my photos. I would sit by the window and sketch them as accurately as possible. I would notice shadows and details I never did before. I wasn’t very good at drawing faces or hands, so I would just skip over those parts, and the ambiguity would add something different and exciting to the sketch. When I looked at the final piece, I liked the interpretation. I liked that it didn’t look exactly like the photo or even realistic. It resembled something of a dream. Perhaps that is what it felt like when I thought back to that memory. And even more so, I enjoyed listening to others’ interpretations of them.

I realized that the idea of not being “good” held me back from doing the things I enjoyed in life. This also holds for photography; ever since I began that journey, I have been drawn to a particular aesthetic similar to my paintings in that it is ethereal, vaguely realistic, and avoids the obvious. But in photojournalism, the images must precisely capture what is happening at the time. I started taking the pictures that other "successful" photographers were taking or that I thought people would like to see. Although I took the images I liked, I never shared them. It wasn’t until I sat down with an editor for a portfolio review that he said, “You’re showing me the pictures you think I want to see. Come back with the photos you like, and then we’ll talk.” So I did, and he liked them. This was a key turning point in really defining my style and regaining my freedom to take the photos I wanted.

People frequently advise students to "learn how to do something and then break the rules." The opposite is true for me. Never learn the rules in the beginning if you want to be truly creative and free to experiment without boundaries. When you do, you establish restrictions from the start, where are you supposed to go from there? You will only ever create within those boundaries. If you allow freedom from the beginning, you can find your truest style and point of view. When children are given a medium, you can see how confidently they use it to create anything. Is it good? Some of the time, sure. Most of the time, probably not. But the essence of art is simply doing it. And that is the memory from when I was a child that I cling to as I filled my sketchbooks.

My father let me use his camera when I first started learning about photography. He didn’t tell me what I should or shouldn’t take photos of or how to get the ‘perfect picture.’I used to spend a lot of time in the backyard taking pictures of myself while experimenting with different settings. I started using that knowledge when I learned what poses looked interesting or how a different shutter speed causes a slight blur in the image. My love for photography was rooted in curiosity and sustained because I knew nothing. However, this applies to everything, not just photography, and painting—playing a musical instrument, for instance. You do not need to be good at your hobbies, as long as it brings you joy.

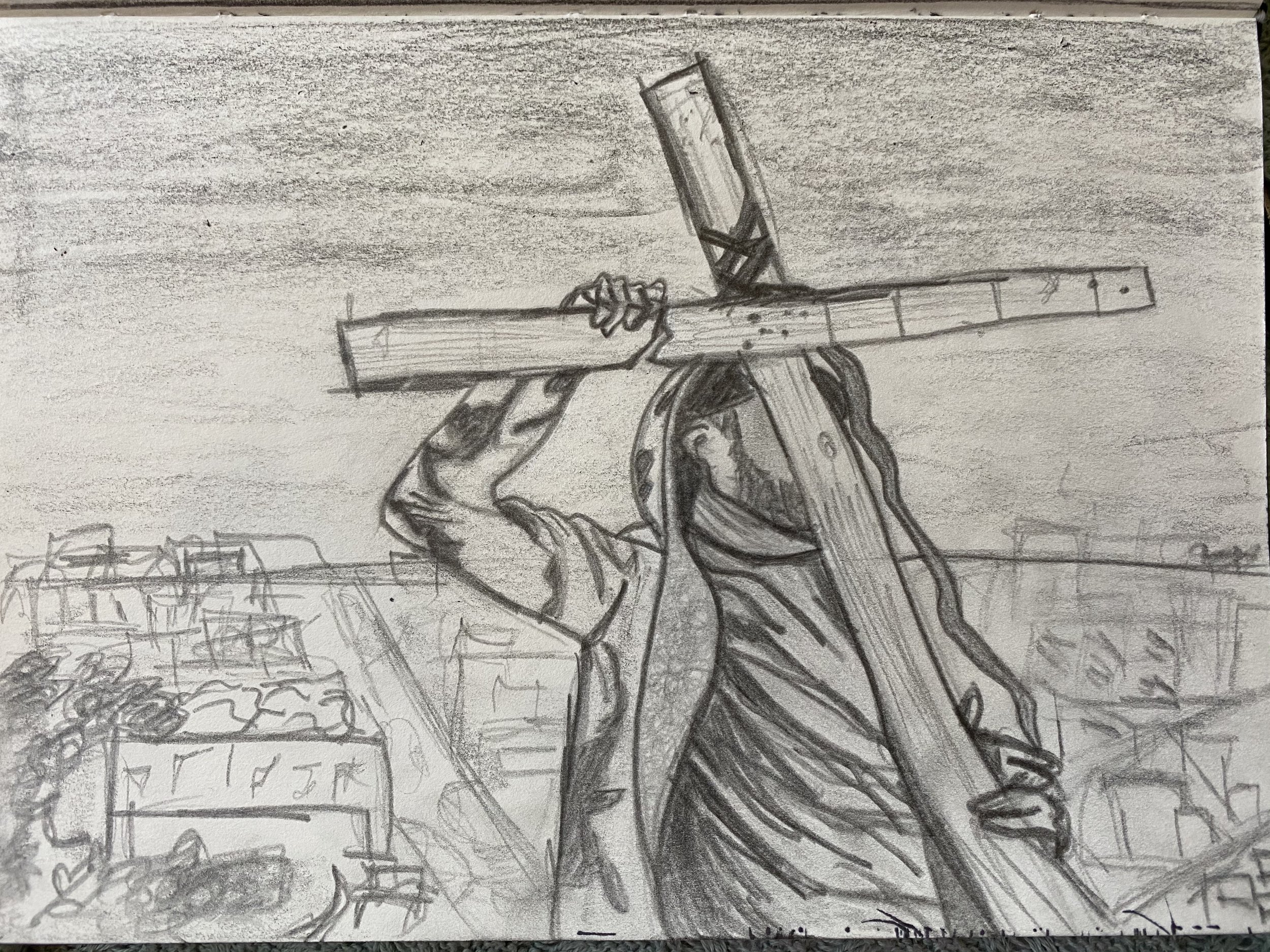

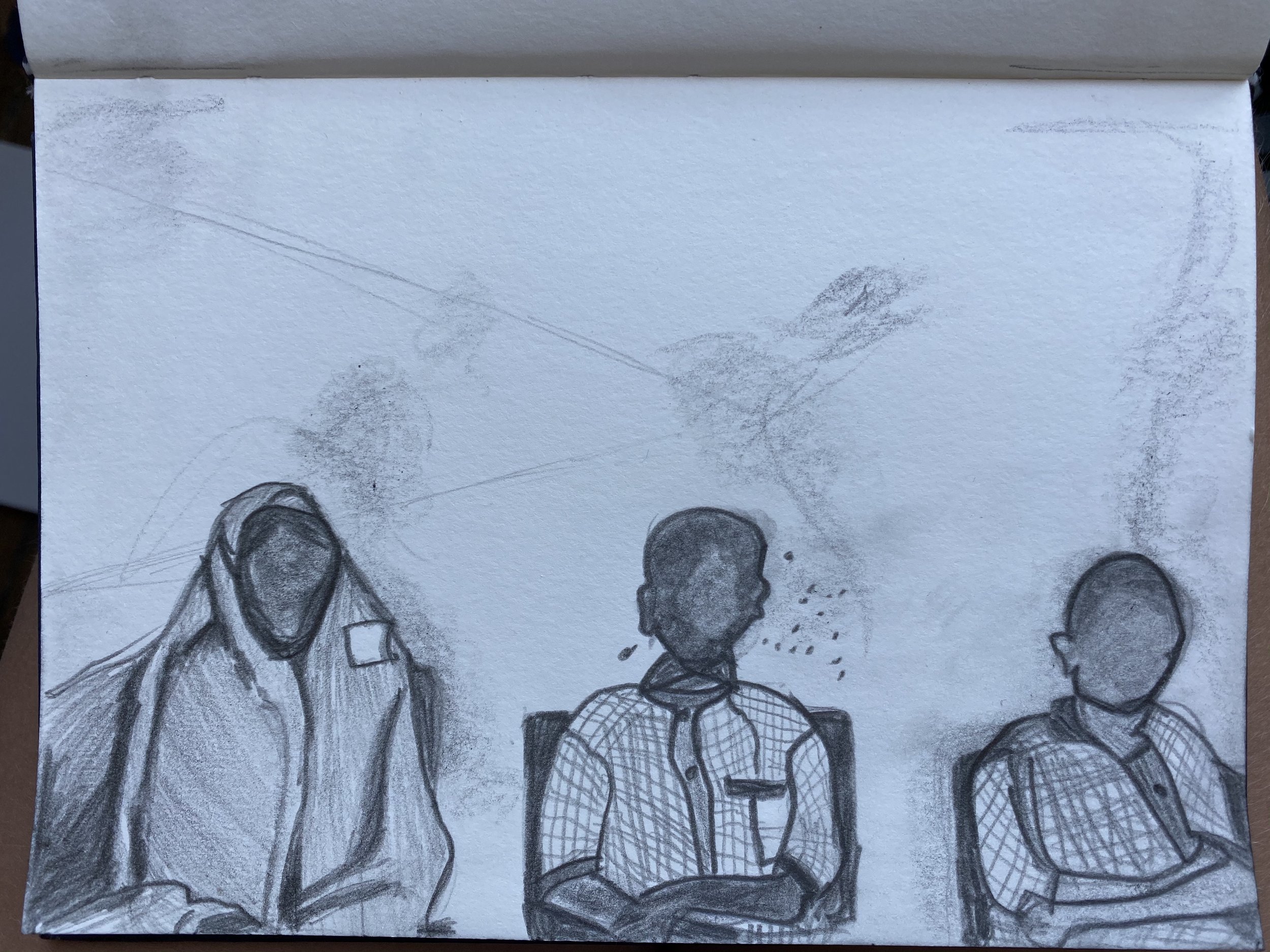

images from the beginning of 2020

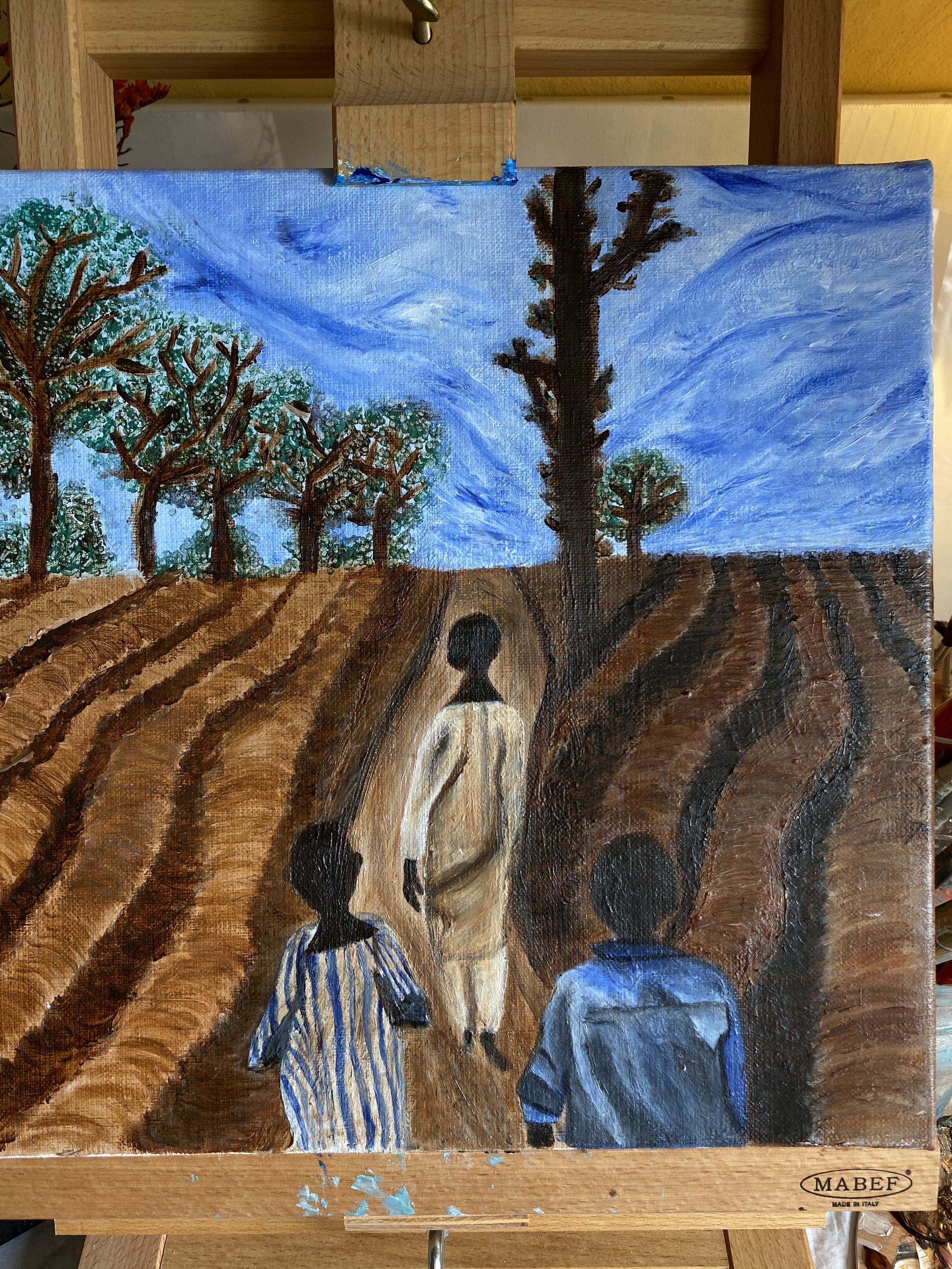

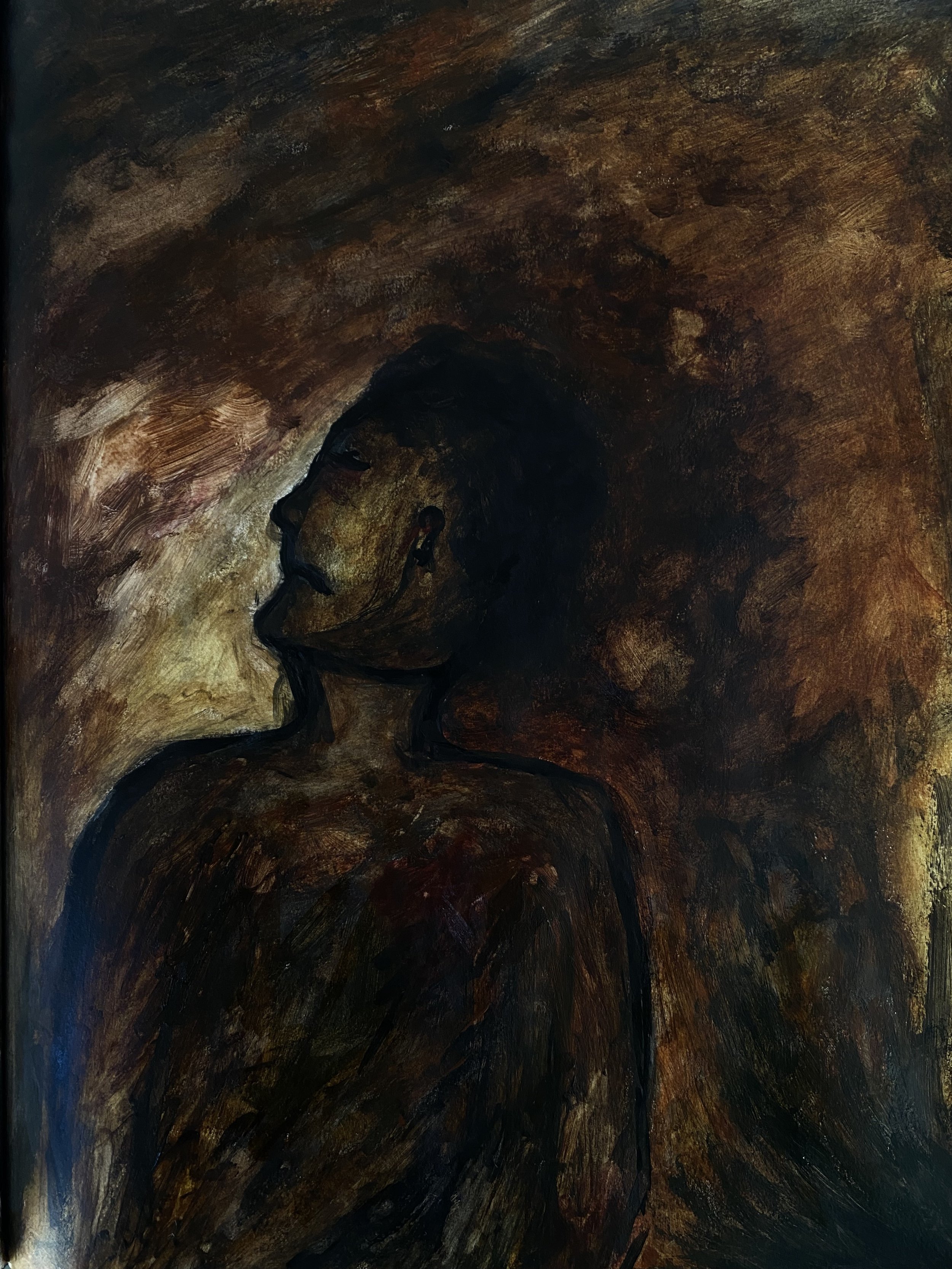

some more recent paintings